The Freelancer's Armor: Why You Should Never Work Without a Contract

Published on: by: Chip Olson

You have calculated your hourly rate. You know the minimum you need to charge to build a sustainable business. That number is your foundation. But a foundation with no structure built on top of it is useless.

A rate without a contract is just a hopeful suggestion.

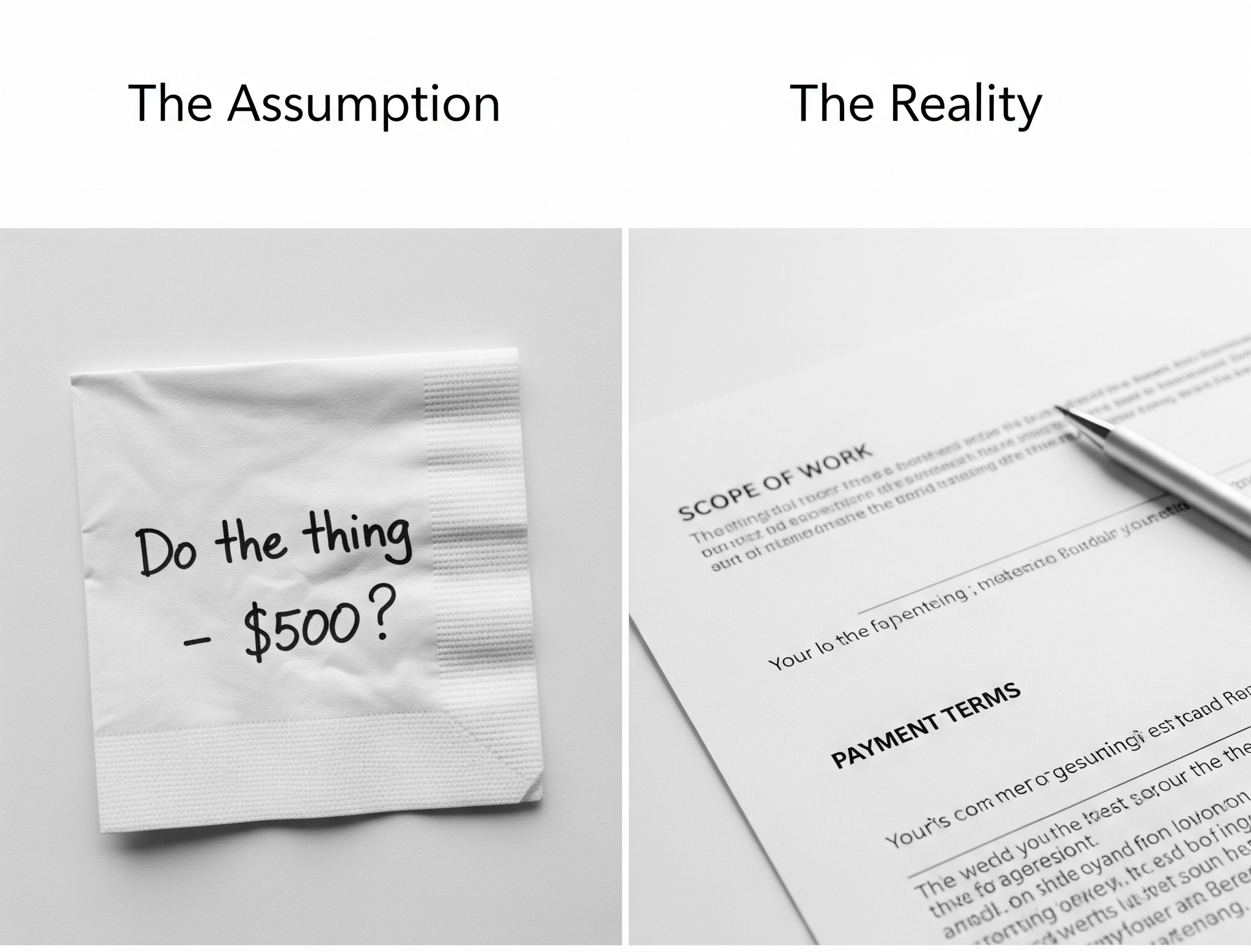

Many freelancers, particularly those new to the field, avoid contracts. They feel it shows a lack of trust or that it will intimidate a potential client. This is a critical business error. A verbal agreement or a casual email chain is a blueprint drawn on a napkin—easily wiped away, misinterpreted, or ignored.

A contract is not a weapon; it is your most important business tool. It is a professional document that eliminates ambiguity and establishes you as a serious business owner. This post will detail the essential components of that tool.

The Purpose of a Contract: It's About Clarity, Not Mistrust

A client who is hesitant to sign a clear, fair contract is a major red flag. Professionals use contracts to ensure clarity. The goal is not to prepare for a conflict, but to prevent one from ever happening.

Early in my consulting career, I learned this lesson the hard way. I developed a comprehensive business expansion plan for a prospective client in the RV industry. I spent weeks on market research and systems analysis, confident that my detailed strategy would lead to a major implementation project. We had a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) in place, so I presented the full plan—the 'how' and the 'why'—assuming they would then hire me to do the work.

They didn't. They took the entire strategic outline I had built and gave it to their internal team to execute.

The NDA prevented them from sharing my plan with their competitors, but it did nothing to ensure I was paid for my strategic labor. They got my best ideas for free. That was a costly but valuable lesson: a contract must define the exchange of value. An NDA protects secrecy; a proper Service Agreement or Statement of Work ensures you get paid for your work—and for your intellectual property.

A contract's primary functions are to:

- Define the Deliverable & Protect Your IP: It defines exactly what the client receives for their money. In my RV case, a contract for a "Phase 1: Strategy" would have defined the deliverable as "one strategic expansion plan document" for a set fee, with terms on how they could use that intellectual property.

- Ensure You Get Paid: It outlines how much, when, and how you will be paid. It turns your strategy and your time into billable assets.

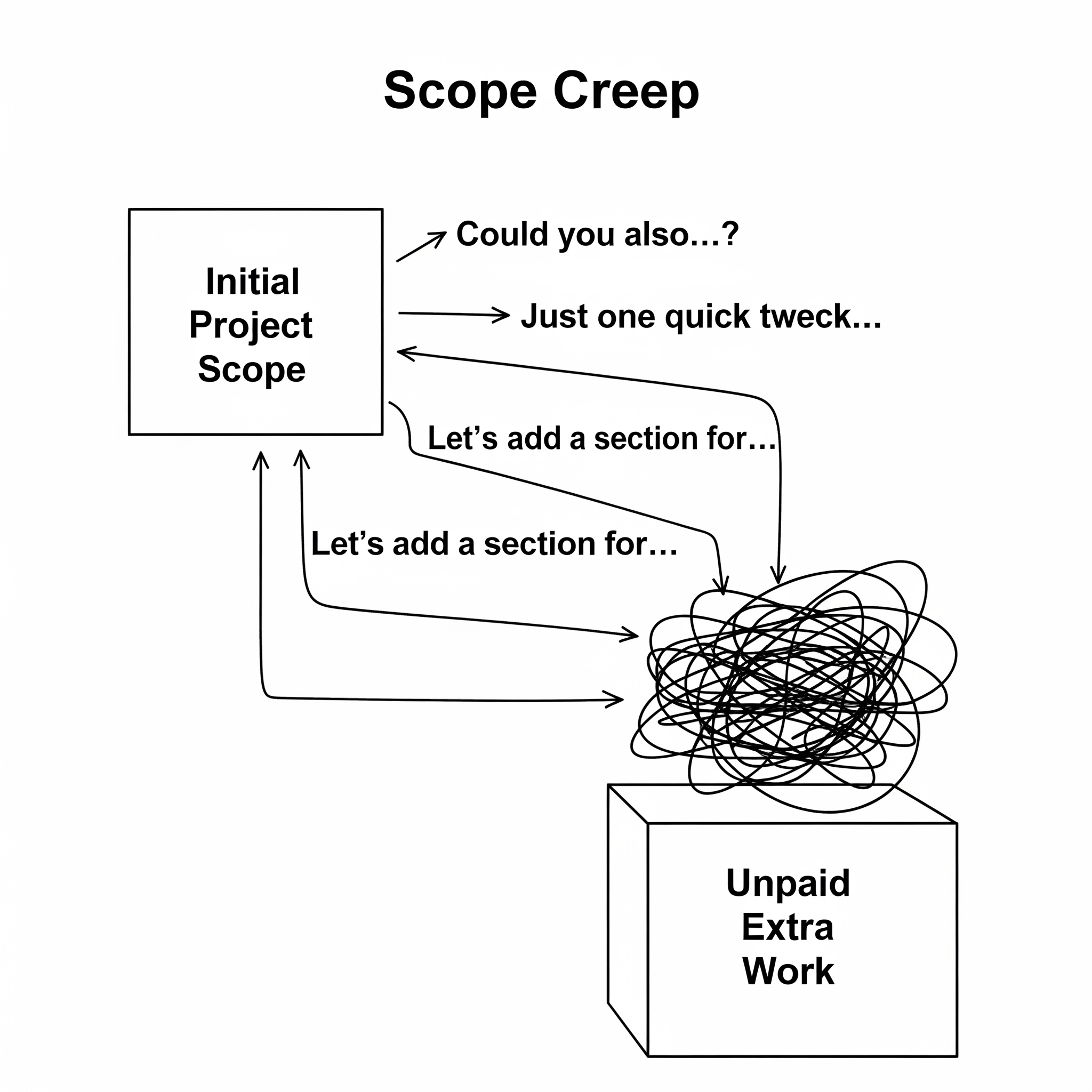

- Prevent "Scope Creep": It creates a clear boundary around the work you agreed to do, preventing clients from endlessly asking for "one more small thing" without additional compensation.

The Anatomy of a Solid Freelance Contract

Every clause in a contract exists because a freelancer somewhere learned a hard lesson. Ensure every contract you use includes these essential sections.

1. Your Details and the Client's Details

This seems obvious, but it is critical. Include the full legal names and addresses of both you (or your business) and the client.

2. The Scope of Work (The "What")

This is the most important section. Be specific to the point of being pedantic. Vague descriptions lead to unpaid work.

- Poor Example: "Write blog posts for the client."

- Good Example: "Deliver three (3) 1200-word blog posts per month on topics provided by the client. Each post will include SEO keyword research for one primary keyword and two secondary keywords. This scope does not include sourcing images or uploading posts to the client's CMS."

3. Deliverables and Milestones (The "When")

Clearly define what the final output will be and when it will be delivered. For larger projects, break it down into milestones.

- Deliverable: The final, tangible product (e.g., "A 10-page website design in Figma," "A strategic expansion plan in PDF format").

- Milestones: Break a large project into phases with their own deadlines (e.g., "Milestone 1: Wireframes - July 15," "Milestone 2: High-Fidelity Mockups - July 30").

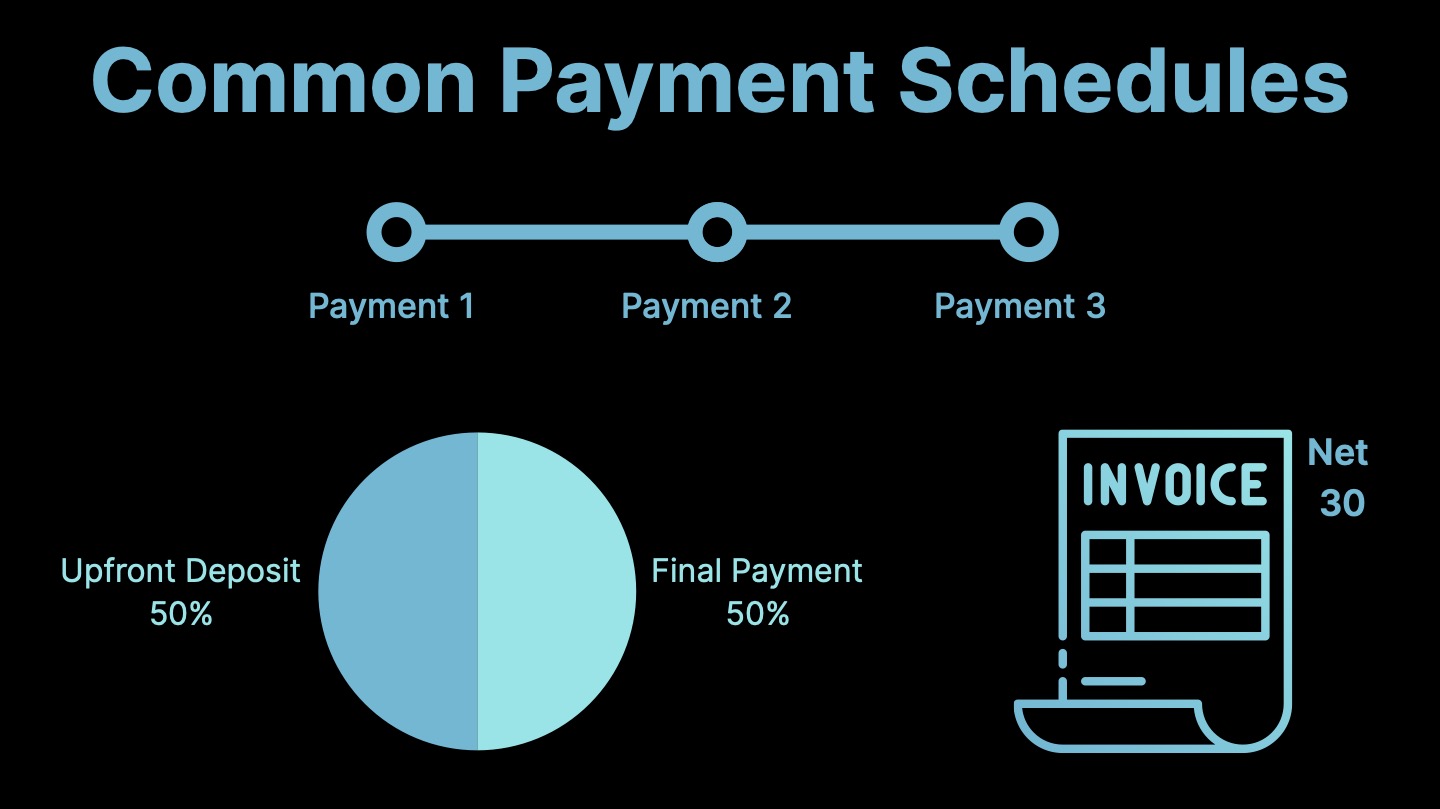

4. Payment Terms (The "How Much")

Be direct and unambiguous about money.

- Rate: State the total project fee or the agreed-upon hourly rate.

- Payment Schedule: Never wait until the end of a large project to get paid. A 50% upfront deposit is standard practice.

- Late Fee Clause: A simple sentence stating that overdue invoices will incur a late fee (e.g., "Invoices unpaid after 30 days will be subject to a 1.5% monthly service charge").

5. Revisions and Feedback

Scope creep often hides in endless feedback loops. Define your revision process clearly.

- Number of Rounds: Specify how many rounds of revisions are included (e.g., "Two (2) rounds of reasonable revisions are included...").

- Additional Revisions: State the cost for any revisions beyond the included rounds (e.g., "Additional revisions will be billed at the standard hourly rate of $X.").

6. Ownership & Usage Rights (The "Who Owns It")

This is a key legal point. The standard practice is that the client owns the final work after you have received final payment in full. You should also explicitly state that you retain the right to display the work in your professional portfolio.

7. Termination Clause (The "Escape Hatch")

Sometimes projects do not work out. This clause defines how to end the relationship professionally, including what happens to work already completed and payments already made.

8. Independent Contractor Clause

In the US, it is important to clarify your work status. Include a sentence that states you are performing services as an independent contractor, not an employee, and you are solely responsible for your own taxes.

How to Get a Contract

You do not need to hire a lawyer for every project.

- Use a Reputable Online Service: Tools built for freelancers like Bonsai or HoneyBook include vetted contract templates.

- Consult a Lawyer Once: After my early mistake with the RV company, I invested in having a lawyer draft a master service agreement. It has saved me tens of thousands of dollars in unpaid work and disputes. It was the most profitable investment I have made in my business.

Conclusion

Your hourly rate, calculated with care using a tool like our Freelance Hourly Rate Calculator, sets your value. A contract is the armor that protects it. It is not an administrative burden; it is a tool for clear communication, professional conduct, and financial security. Do not start work without one.

- Chip Olson